Astronomers have identified a star system with three Super-Earths and two Super-Mercuries, a form of planet that is exceptionally rare and unique. In fact, super-Mercuries are so uncommon that only eight have been discovered to date.

ESPRESSO’s spectrograph detected two ‘super-Mercury’ worlds in the star system HD 23472. Astronomers have discovered that these planets are extremely rare. This study, published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, looked at how the composition of tiny planets varies with planet position, temperature, and star attributes.

The reason for observing this planetary system, according to Susana Barros, a researcher at the Institute of Astrophysics e Ciências do Espaço (IA) who led the project, is to characterise the composition of small planets and to study the transition between having an atmosphere and not having an atmosphere.

The evaporation of the atmosphere could be related to star irradiation. “Surprisingly, the team found that this system is composed of three super-Earths with a significant atmosphere and two Super-Mercuries, which are the closest planets to the star,” the researcher revealed.

HD 23472 has five exoplanets, three of which have masses less than that of the Earth. The five planets were discovered to be among the lightest exoplanets ever detected using the radial velocity approach. This approach can detect minor fluctuations in a star’s velocity produced by orbiting planets.

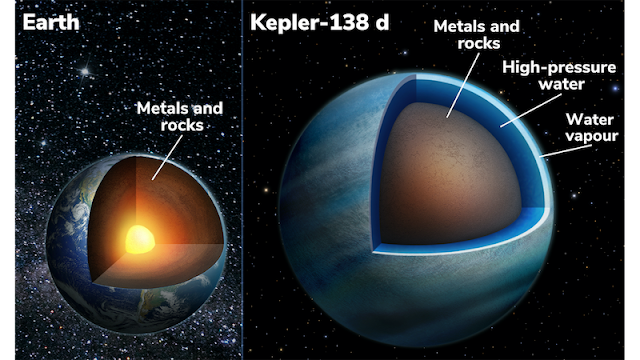

The high accuracy that permitted the finding was provided by ESPRESSO, a spectrograph situated on the VLT at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Chile. Super-Earths and super-Mercuries are the higher mass analogues to Earth and Mercury in terms of composition. The key distinction between them is that super-Mercuries contain more iron. This form of exoplanet is extremely rare.

In fact, only eight are known, including the two that were recently discovered. We don’t know why Mercury has a larger and more massive core than Earth and the other planets in our Solar System, while being one of the densest planets.

Mercury’s mantle could have been lost by a massive impact, or because Mercury is the hottest planet in the solar system, its high temperatures could have melted some of its mantle. To comprehend the development of such objects, it is necessary to locate other dense, Mercury-like planets orbiting other stars.

It’s worth noting that the discovery of two super-Mercuries in the same planetary system, rather than just one, paints a clear picture for scientists. “We identified a system with two super-Mercuries for the first time utilising the ESPRESSO spectrograph.” This helps us understand how these planets developed,” says Alejandro Suárez, an IAC researcher and co-author of this work.

“The idea of a massive impact creating a Super-Mercury is already extremely implausible; two giant impacts in the same system appears extremely unlikely.” According to co-author and IAC researcher Jonay González, additional characterization of the planet’s composition would be required to comprehend how these two super-Mercuries evolved.

For the first time, scientists will be able to examine the surface composition or the existence of a hypothetical atmosphere using the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) and its first-generation high-resolution spectrograph ANDES. Finally, the team’s ultimate goal is to discover another planet like Earth.

Scientists can better comprehend the origin and evolution of planetary systems because of the presence of an atmosphere. It can also determine whether a planet is habitable. “We would like to continue this type of investigation to longer period planets with more suitable temperatures,” Barros says.

.png)