The light of a star that lived during the first billion years after the universe's beginning in the big bang has been detected by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope - the farthest individual star ever observed to date.

The discovery represents a significant step back in time from the previous single-star record holder, which was discovered by Hubble in 2018. That star lived around 4 billion years ago, or 30 percent of the universe's present age.

The newly discovered star is so far away that its light has taken 12.9 billion years to reach Earth, so we are viewing it when the cosmos was only 7% the age it is now. Clusters of stars nested within early galaxies are the tiniest things hitherto discovered at such a long distance.

“We almost didn’t believe it at first, it was so much farther than the previous most-distant, highest redshift star,” said astronomer Brian Welch of the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, lead author of the paper describing the discovery in the journal Nature. Scientists use the word “redshift” because as the universe expands, light from distant objects is stretched or “shifted” to longer, redder wavelengths as it travels toward us.

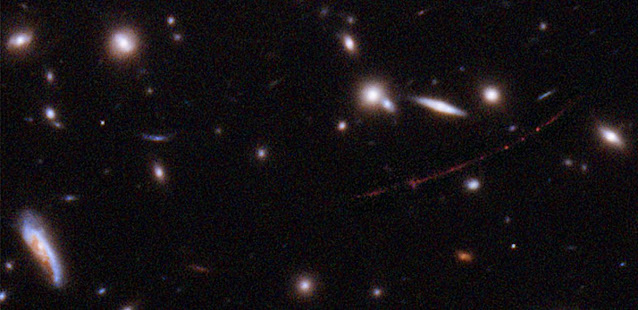

“Normally at these distances, entire galaxies look like small smudges, with the light from millions of stars blending together,” said Welch. “The galaxy hosting this star has been magnified and distorted by gravitational lensing into a long crescent that we named the Sunrise Arc.”

Welch concluded that one feature of the galaxy is an extraordinarily magnified star he named Earendel, which means "dawn star" in Old English. The discovery has the potential to usher in a hitherto unknown era of very early star creation.

“Earendel existed so long ago that it may not have had all the same raw materials as the stars around us today,” Welch explained. “Studying Earendel will be a window into an era of the universe that we are unfamiliar with, but that led to everything we do know.”

“It’s like we’ve been reading a really interesting book, but we started with the second chapter, and now we will have a chance to see how it all got started,” Welch said.

When the Planets Align

According to the researchers, Earendel is at least 50 times the mass of our Sun and millions of times brighter, rivalling the most massive stars known.

Even a dazzling, extremely high-mass star would be hard to detect at such a long distance without the natural magnification provided by WHL0137-08, a massive galaxy cluster located between us and Earendel. The galaxy cluster's bulk warps the fabric of space, forming a powerful natural magnifying glass that distorts and considerably amplifies light from distant objects behind it.

The star Earendel appears directly on, or quite close to, a ripple in the fabric of space due to a unique alignment with the magnifying galaxy cluster. This ripple, known as a "caustic" in optics, gives maximum magnification and brightness. On a sunny day, the rippling surface of a swimming pool creates patterns of dazzling light on the bottom of the pool. The surface ripples work as lenses, focusing sunlight to maximum brightness on the pool bottom.

Because of this caustic, the star Earendel stands out from the ambient brilliance of its parent galaxy. Its radiance is multiplied a thousand times or more. At the moment, astronomers are unable to tell if Earendel is a binary star, despite the fact that most big stars have at least one smaller partner star.

Webb's confirmation

Astronomers anticipate that Earendel will remain highly amplified for many years. NASA's new James Webb Space Telescope will observe it. Webb's exceptional sensitivity to infrared light is required to learn more about Earendel because the universe's expansion causes its light to be stretched (redshifted) to longer infrared wavelengths.

“With Webb we expect to confirm Earendel is indeed a star, as well as measure its brightness and temperature,” said co-author Dan Coe at Baltimore’s Space Telescope Science Institute, who made the discovery using the data collected.

These details will narrow down its type and stage in the stellar lifecycle, with scientists expecting it to be a “rare, massive metal-poor star,” Coe said.

Astronomers will be fascinated by Earendel's composition because it formed before the universe was filled with heavy elements created by successive generations of huge stars. If further research reveals that Earendel is only composed of primordial hydrogen and helium, it would be the first evidence for the legendary Population III stars, which are thought to be the very first stars born after the big bang. While the likelihood is remote, Welch concedes it is alluring.

“With Webb, we may see stars even farther than Earendel, which would be incredibly exciting,” Welch said. “We’ll go as far back as we can. I would love to see Webb break Earendel’s distance record.”

Credit: NASA, ESA, Brian Welch of JHU, and Dan Coe of STScI

Reference(s): Nature

.jpg)