The Hubble Space Telescope has reportedly reached a new milestone in its quest to measure the speed at which the universe is expanding, and it strongly suggests that something strange is going on in our cosmos.

Astronomers have recently utilised telescopes like Hubble to measure how quickly the cosmos is expanding.

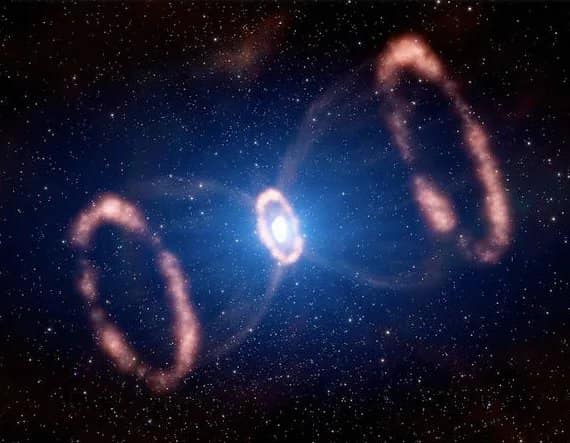

However, as the data were refined, a peculiar finding was made. There is a considerable gap between evidence from the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang and the universe's current rate of expansion.

Scientists have been unable to explain the discrepancy. However, it shows that "something weird" is going on in our cosmos, which might be the product of undiscovered, new physics, according to NASA.

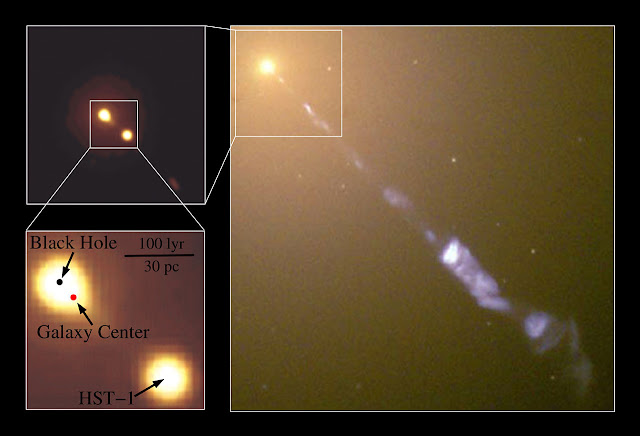

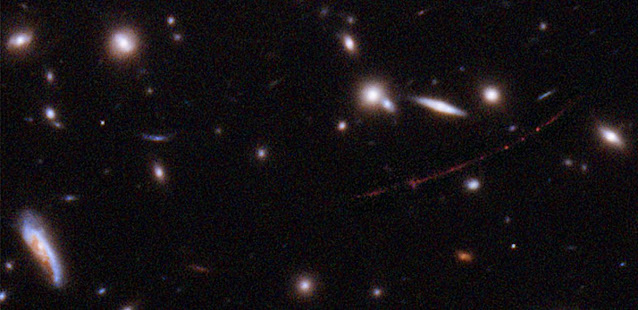

Hubble has spent the last 30 years collecting data on a set of "milepost markers" in space and time that can be used to trace the expansion rate of the cosmos as it moves away from us.

According to NASA, it has now calibrated more than 40 of the markers, allowing for even more precision than previously.

In a statement, Nobel Laureate Adam Riess of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, stated, "You are getting the most precise measure of the expansion rate for the universe from the gold standard of telescopes and cosmic mile markers."

He is the leader of a group of scientists who have released a new research paper detailing the largest and most likely last significant update from the Hubble Space Telescope, tripling the previous set of mile markers and reanalysing existing data.

The hunt for a precise estimate of how quickly space was expanding began when American astronomer Edwin Hubble saw that galaxies beyond our own appeared to be moving away from us – and moving faster the further away they are. Since then, scientists have been working to gain a deeper understanding of that growth.

In honour of the astronomer's effort, both the rate of expansion and the space telescope that has been studying it are named Hubble.

When the space telescope began gathering data on the universe's expansion, it was discovered to be faster than models had expected. Astronomers anticipate that it should be approximately 67.5 kilometres per second per megaparsec, plus or minus 0.5, while measurements suggest that it is closer to 73.

Astronomers have a one in a million probability of getting it incorrect. Instead, it implies that the universe's growth and expansion are more intricate than we previously thought, and that there is still much to discover about how the cosmos is changing.

The newly launched James Webb Space Telescope, which will soon send back its first observations, will be used by scientists to delve deeper into this difficulty. They should be able to see more recent, far-off, and detailed mileposts as a result.

Reference(s): NASA

.jpg)