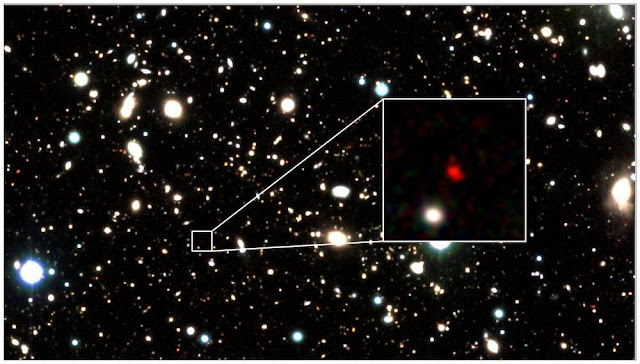

A galaxy named HD1 has been crowned the new farthest object in the cosmos.

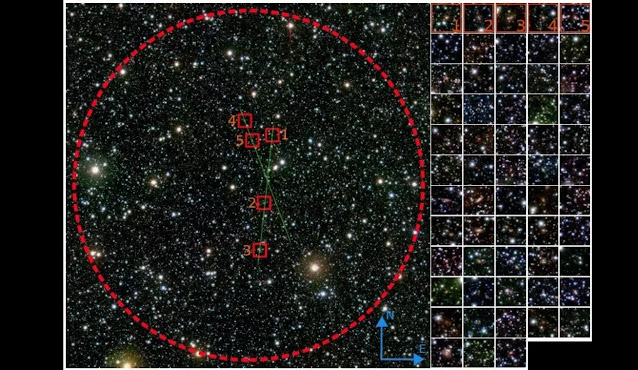

Astronomers may have discovered the most distant galaxy, HD1. Harikane et al.

Located some 13.5 billion light-years away, HD1 existed only about 330 million years after the Big Bang. And the far-flung galaxy may be harboring another surprise, too — either Population III stars, the first stars born in the cosmos, or the earliest supermassive black hole ever found.

The findings are presented in two papers, released today (April 7) in The Astrophysical Journal and the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters (MNRAS).

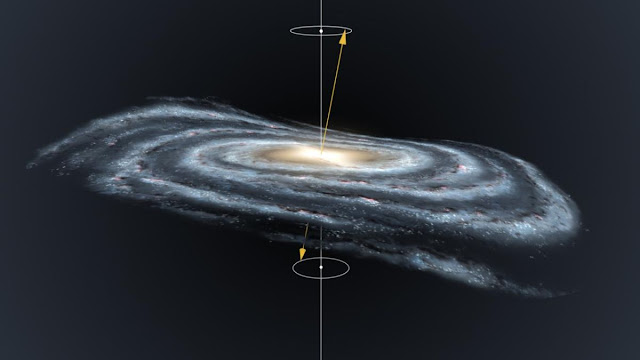

HD1's age compared to the farthest galaxy confirmed to date. Harikane et al., NASA, EST and P. Oesch/Yale.

HD1 is extremely bright in ultraviolet light, which is normally evidence that a galaxy is producing stars at a high rate. But researchers quickly realized that even if HD1 was a starburst galaxy, it would be creating over 100 stars a year.

“This is at least 10 times higher than what we expect for these galaxies,” said Fabio Pacucci, lead author of the MNRAS study, co-author in the discovery paper in The Astrophysical Journal, in a news release.

So the team turned to other possibilities that might explain HD1’s surplus of ultraviolet light.

Population III stars float in primordial gas in this artist's concept of the early universe. NASA/WMAP Science Team

The first stars

One possible explanation for HD1's ultraviolet radiance is that the stars the galaxy is producing are different from the mundane stars produced in modern galaxies. Today, stars are made from recycled material ejected from previous generations of stars. So, every star has some heavier elements, even if just a sprinkle.

But in the very early universe, after the Big Bang, primordial gas consisted entirely of hydrogen, helium, and a sampling of lithium and beryllium. From these elements, the first stars were born. Known as Population III stars, they were more massive, more luminous, and hotter than today’s stars. They also perfected the mantra of live fast, die young, burning out within only a few million years.

The only problem: Population III stars are hypothetical as their quick lives means no direct evidence of them has ever been spotted. But the recent discovery of the earliest star, Earendel, may prove fruitful for Population III hunters — if follow-up studies find the star’s composition to be entirely hydrogen and helium.

In the meantime, while Population III stars would easily explain HD1’s brightness in the ultraviolet wavelength, they aren’t the only possibility.

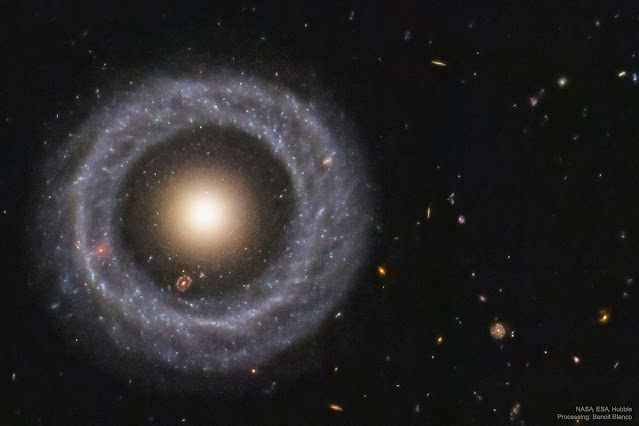

An artist's concept of a galaxy in the early universe. The bright center is a quasar — highly luminous objects powered by supermassive black holes. ESO/M. Kornmesser

Earliest cosmic monster

Alternatively, a supermassive black hole might explain the galaxy's ultraviolet brightness. If that's the case, the supermassive black hole would become the earliest known, breaking the previous record by some 500 million years.

Supermassive black holes are believed to reside in the hearts of most galaxies, but understanding how these monsters grew so big so quickly in the early universe remains a conundrum for scientists. Physics tells us that black holes need time to gobble up enough material to grow to supermassive proportions, meaning that scientists didn’t expect to see them so early in the cosmic timeline.

But in 2017, astronomers began finding these monsters within the universe’s earliest galaxies. Disks of material surrounded the black holes, and the infalling matter shone so brightly the galaxies, despite their extreme distances, can still be seen today.

It is the high-energy photons from that infalling material, which gets violently swirled around the black hole, that might be causing HD1’s ultraviolet brightness.

“Forming a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, a black hole in HD1 must have grown out of a massive seed at an unprecedented rate,” explains MNRAS co-author Avi Loeb. Such an early black hole may not answer the question of how these objects grew so big so quickly, but it would narrow down how soon they appeared in the early universe.

JWST up to bat

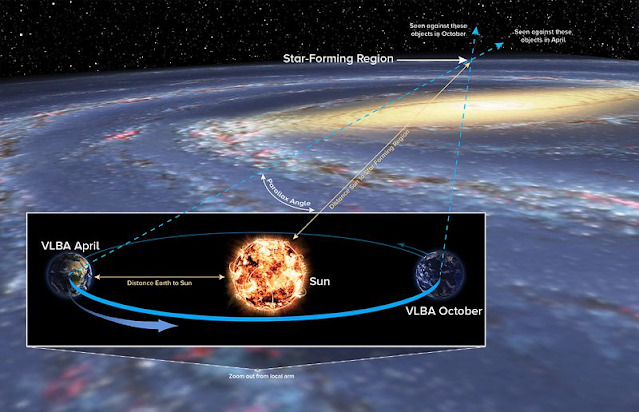

To make this distant discovery, the team spent more than 1,200 hours observing with the Subaru Telescope, VISTA Telescope, UK Infrared Telescope, and Spitzer Space Telescope. To verify HD1's distance, the team plans to observe the galaxy again, this time with NASA’s powerful James Webb Space Telescope.

Capable of peering back to the first luminous glows that emerged after the Big Bang, JWST will also be able to settle which theory explains HD1's ultraviolet shine. And, perhaps, find even more distant galaxies in the earliest moments of the cosmos.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)