We’re one step closer to a future of near-limitless clean energy.

Physicists in Germany just found a way to minimize a major heat-loss problem plaguing a promising kind of nuclear fusion reactor called a “stellarator.”

The future of clean energy: Nuclear fusion occurs when the nuclei of two atoms merge into one. This releases an enormous amount of energy — it’s literally enough to power the sun and other stars.

If we could harness the power of nuclear fusion on Earth, it would be an absolute game changer in the battle against climate change.

Recreating fusion on Earth requires scientists to “put the sun in a box.”

Fusion doesn’t produce any carbon emissions (like the burning of fossil fuels) or long-lasting radioactive waste (like nuclear fission), and unlike solar and wind power, it isn’t dependent on the weather.

Designing a nuclear fusion reactor: Nuclear fusion can only happen under extreme heat and pressure — Nobel-winning physicist Pierre-Gilles de Gennes once said recreating it on Earth would require scientists to essentially put the “sun in a box.”

Scientists have designed a few different “boxes” — nuclear fusion reactors — that can create the conditions needed for fusion, but they require more energy than they produce, and until that changes, fusion won’t be a viable source of power.

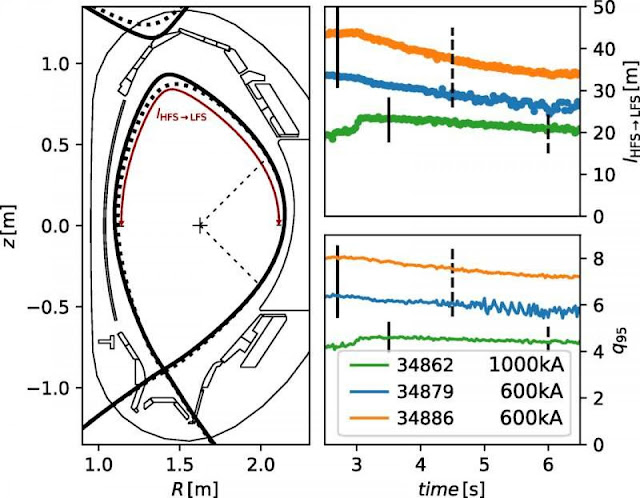

Stellarators 101: A stellarator is a type of nuclear fusion reactor that looks like a massive donut that has been squished and twisted out of shape. A coil of magnets surrounds the stellarator, creating magnetic fields that control the flow of plasma within it.

By subjecting this plasma to extreme temperatures and pressure, a stellarator can force atoms within it to undergo fusion, and compared to other fusion reactors, stellarators require less power and have more design flexibility.

However, the device’s design makes it easier for the plasma to lose heat through a process called “neoclassical transport” — and without heat, you can’t have sustained fusion.

“It’s really exciting news for fusion that this design has been successful.”

NOVIMIR PABLANT

What’s new? Now, researchers have reduced heat loss in the world’s largest and most advanced stellarator — called the Wendelstein 7-X — by optimizing its magnetic coil.

In doing so, they were able to heat the interior of their nuclear fusion reactor to nearly 54 million degrees Fahrenheit — that’s more than twice as hot as the sun’s core — and testing confirmed that their design had specifically minimized heat loss due to neoclassical transport.

“It’s really exciting news for fusion that this design has been successful,” physicist Novimir Pablant said. “It clearly shows that this kind of optimization can be done.”

And now, stellarators are one step closer to being a usable design for a nuclear fusion reactor.